We’re lucky when criminal justice data is broken down by race and ethnicity enough to see how Native populations are criminalized and incarcerated. Here’s a roundup of what we know from Prison Policy Initiative:

The U.S. criminal justice system disproportionately hurts Native people: the data, visualized

We’re lucky when criminal justice data is broken down by race and ethnicity enough to see how Native populations are criminalized and incarcerated. Here’s a roundup of what we know.

by Leah Wang, October 8, 2021

This Monday is Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a holiday dedicated to Native American people, their rich histories, and their cultures. Our way of observing the holiday: sending a reminder that Native people are harmed in unique ways by the U.S. criminal justice system. We offer a roundup of what we know about Native people (those identified by the Census Bureau as American Indian/Alaska Native) who are impacted by prisons, jails, and police, and about the persistent gaps in data collection and disaggregation that hide this layer of racial and ethnic disparity.

The U.S. incarcerates a growing number of Native people, and what little data exist show overrepresentation

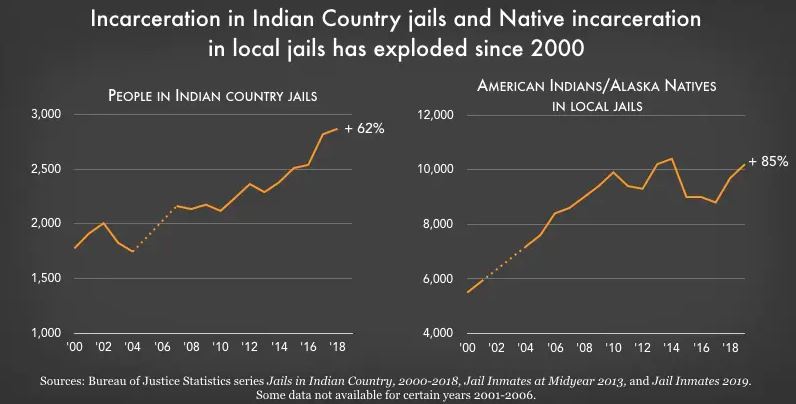

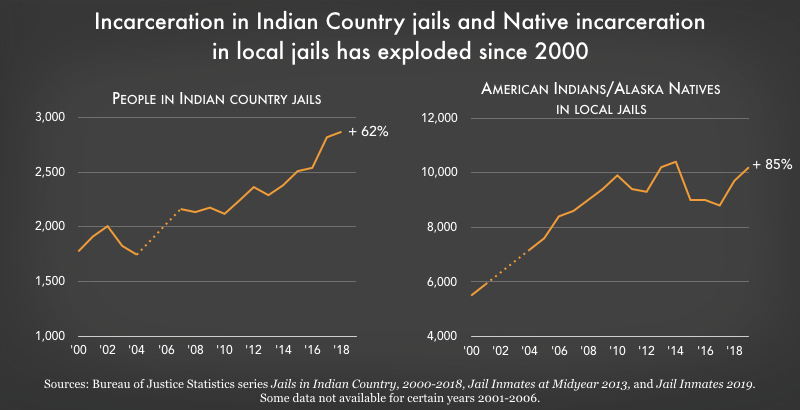

In 2019, the latest year for which we have data, there were over 10,000 Native people locked up in local jails. Although this population has fluctuated over the past 10 years, the Native jail population is up a shocking 85% since 2000. And these figures don’t even include those held in “Indian country jails,” which are located on tribal lands: The number of people in Indian country jails increased by 61% between 2000 and 2018. Meanwhile, the total population of Native people living on tribal lands has actually decreased slightly over the same time period, leaving us to conclude that we are criminalizing Native people at ever-increasing rates.

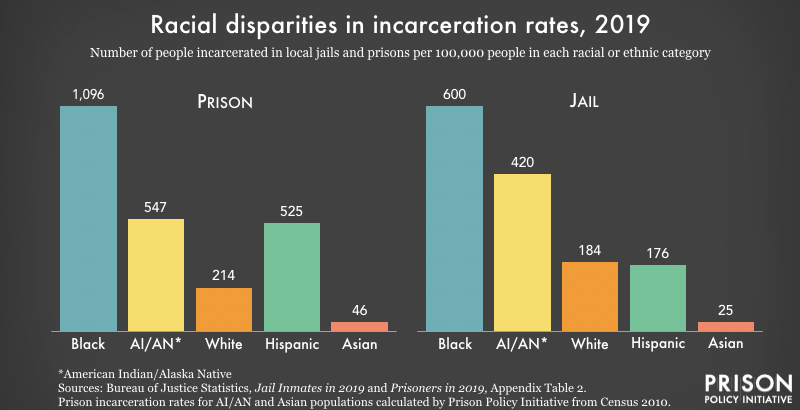

Native people made up 2.1% of all federally incarcerated people in 2019, larger than their share of the total U.S. population, which was less than one percent. Similarly, Native people made up about 2.3% of people on federal community supervision in mid-2018. The reach of the federal justice system into tribal territory is complex: State law often does not apply, and many serious crimes can only be prosecuted at the federal level, where sentences can be harsher than they would be at the state level. This confusing network of jurisdiction sweeps Native people up into federal correctional control in ways that don’t apply to other racial and ethnic groups.

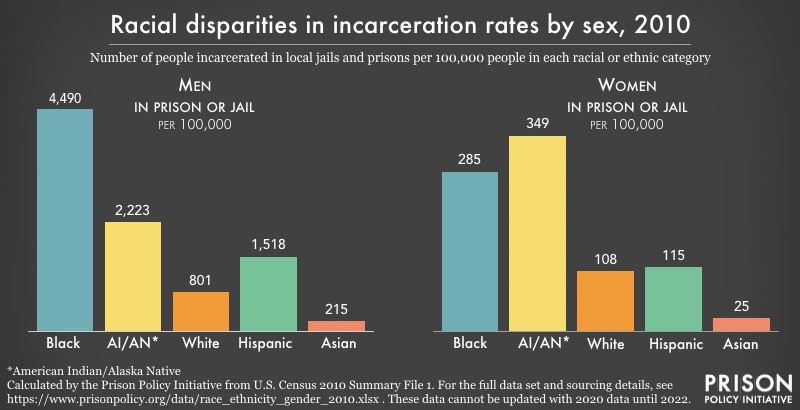

Native women are particularly overrepresented in the incarcerated population: They made up 2.5% of women in prisons and jails in 2010, the most recent year for which we have this data (until the 2020 Census data is published); that year, Native women were just 0.7% of the total U.S. female population. Their overincarceration is another maddening aspect of our nation’s contributions to human rights crises facing Native women, in addition to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and high rates of sexual and other violent victimization.

Confinement of Native youth is a crisis

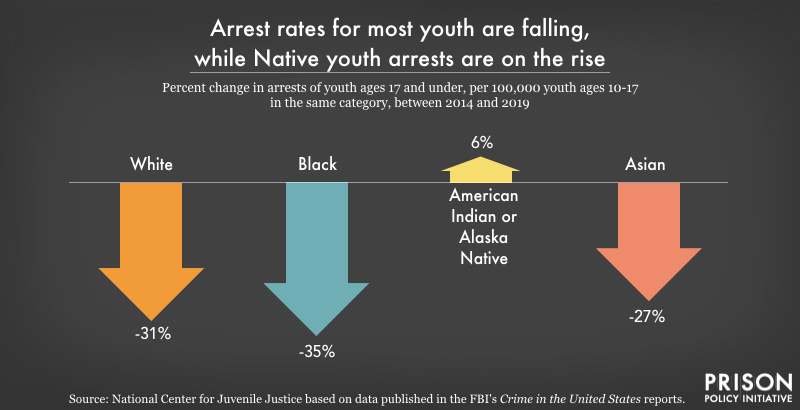

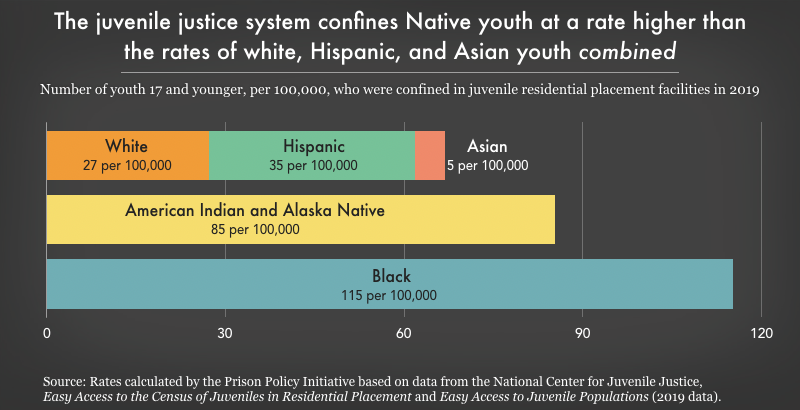

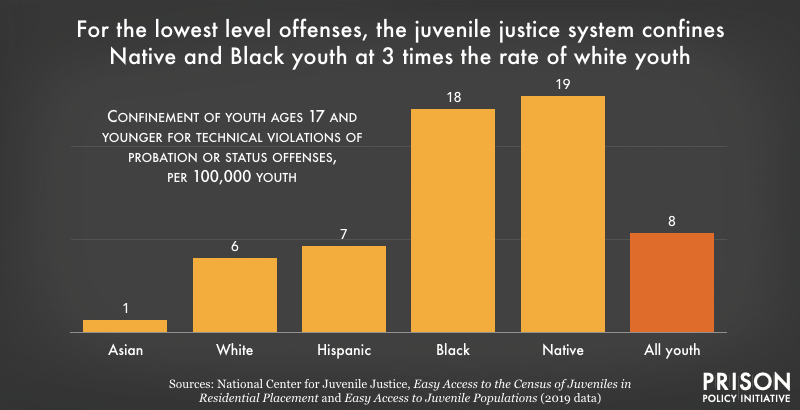

The rampant racial disparities in how Native youth are treated by the juvenile and criminal justice system are somewhat better-documented. Their confinement rates, second only to those of Black youth, exceed those of white, Hispanic and Asian youth combined. Forces contributing to this disparity include disproportionate arrest rates of Native youth for some offense types, the school-to-prison pipeline, and harsher outcomes for court-involved youth, particularly for low-level offenses like technical violations of probation and status offenses.

In absolute numbers, there are fewer Native youth than there are white, Black, Hispanic, or Asian youth, but the rate at which they are in contact with police and youth confinement facilities is alarming. Centuries of historical trauma are manifesting in Native youth as mental health and substance use issues that go untreated, and can lead to status offenses (acts that are only criminal because of one’s age, like skipping school) or other “delinquent” behavior. Once again, federal jurisdiction over tribal lands makes Native youth worse off for being swept up into criminal-legal matters at all, because they’re more likely to receive longer federal sentences and less likely to receive the services and support they need.

Even the best data collection obscures the scale and scope of Native people in the criminal justice system

There is still a long way to go to attain consistent data collection and reporting on Native populations in the criminal justice system. One glaring problem is that pesky “Other” category where we sometimes find Asian, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian, and American Indian/Alaska Native people. This is clearly an unhelpful category for uncovering bias throughout policing, courts, jails, prisons, and supervision.

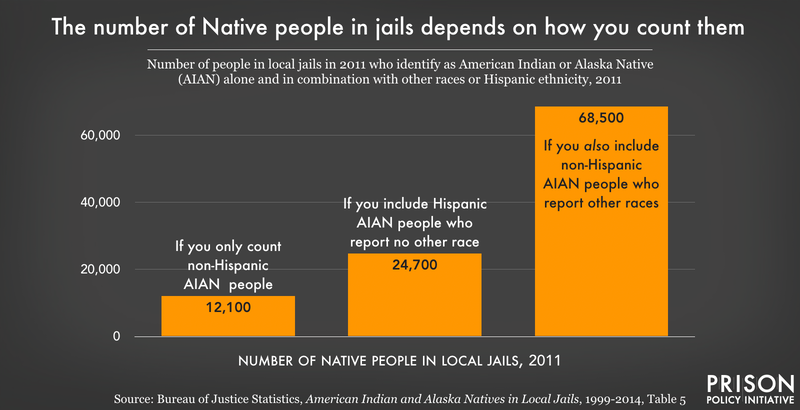

One reason that even our most disaggregated data falls short is that often, people reporting two or more races are lumped into various categories depending on who is publishing the data. In 2011, the latest year for which we have this data, the single-race American Indian/Alaska Native jail population was 12,100 while the total number of people who included a Native identity was over 70,000. This reporting makes it clear that Native people are overrepresented among the incarcerated populations, but we don’t always see the data presented in a way that highlights this disparity.

Footnotes

- The Native population in local jails was 10,200 in 2019, up from 5,500 in 2000 – an 85% increase. The growth of the Native population in jails far outpaced the growth of the total jail population over the same period: Overall, local jail populations grew 18% from 2000 to 2019. (Before 2000, in reporting jail populations, the Bureau of Justice Statistics combined the American Indian/Native Alaskan population with Asians, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders into an “Other” category.) ↩

- The term “Indian country,” in this context, is a legal term referring to land within American Indian reservations and other Native communities and allotments. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects and publishes data about jail facilities on these lands separately from other locally-operated jails in the U.S. According to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the term “Indian Country” – with a capital “C” – “is used with positive sentiment within Native communities, by Native-focused organizations such as NCAI, and news organizations such as Indian Country Today.” ↩

- Based on U.S. Census Bureau population estimates of people identifying as non-Hispanic, and American Indian/Native Alaskan alone or in combination with one or more other races. ↩

- The remote nature of tribal lands in relation to federal buildings like courthouses, parole offices and prisons also makes it difficult to comply with post-release supervision, make court dates, or visit incarcerated loved ones. For the same reason, Native people are consistently underrepresented on federal trial juries, despite being constitutionally mandated to be fairly represented on them. These are examples of how Native people are harmed and shut out by the federal justice system. ↩

- The number of Native women in both the U.S. population and the incarcerated population (defined as non-Hispanic, single-race females) was sourced from the 2010 U.S. Census. ↩

- The “jurisdictional maze” between federal and tribal authorities (described earlier in this briefing) makes it less likely that a crime of sexual violence occurring on tribal land will be prosecuted, leaving victims with little support and little choice but to continue living near those who harm them. ↩

- If you expand the definition of who is Native among the general U.S. population, you’re also going to see an increase, but it’s not nearly as staggering as the six-fold increase between the narrowest and widest definitions of incarcerated Native people. In 2011, the single-race, non-Hispanic AI/AN population would be 2.3 million; including Hispanic AI/AN people would increase this figure to 3.8 million; and including multi-racial AI/AN people would increase the figure to 4.1 million, only a 1.7-fold increase from lowest to highest. ↩

Leah Wang is a Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. (Other articles | Full bio | Contact)