Ms. Lee is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace reporting fellow.

Tommy Munsdwell Canady was in middle school when he wrote his first rap lyrics. He started out freestyling for friends and family, and after two of his cousins were fatally shot, he found solace in making music. “Before I knew it my pain started influencing all my songs,” he told me in a letter. By his 15th birthday, Mr. Canady was recording and sharing his music online. His tracks had a homemade sound: a pulsing beat mixed with vocals, the words hard to make out through ambient static. That summer, in 2014, Mr. Canady released a song on SoundCloud, “I’m Out Here,” that would change his life.

In Racine, Wis., where Mr. Canady lived, the police had been searching for suspects in three recent shootings. One of the victims, Semar McClain, 19, had been found dead in an alley with a bullet in his temple, his pocket turned out, a cross in one hand and a gold necklace with a pendant of Jesus’ face by his side. The crime scene investigation turned up no fingerprints, weapons or eyewitnesses. Then, in early August, Mr. McClain’s stepfather contacted the police about a song he’d heard on SoundCloud that he believed mentioned Mr. McClain’s name and referred to his murder.

On Aug. 6, 2014, about a week after Mr. Canady released “I’m Out Here,” a SWAT team stormed his home with a “no knock” search warrant. Lennie Farrington, Mr. Canady’s great-grandmother and legal guardian, was up early washing her clothes in the kitchen sink when the police broke through her front door. Mr. Canady was asleep. “They rushed in my room with assault rifles telling me to put my hands up,” he recalled. “I was in the mind state of, This is a big misunderstanding.” He was charged with first-degree intentional homicide and armed robbery.

Prosecutors offered Mr. Canady a plea deal, but he refused, insisting he was innocent. “Honestly, I’m not accepting that,” he told the judge. He decided to go to trial.

I have been reporting on the use of rap lyrics in criminal investigations and trials for more than two years, building a database of cases like Mr. Canady’s in partnership with the University of Georgia and Type Investigations. We have found that over the past three decades, rap — in the form of lyrics, music videos and album images — has been introduced as evidence by prosecutors in hundreds of cases, from homicide to drug possession to gang charges. Rap songs are sometimes used to argue that defendants are guilty even when there’s little other evidence linking them to the crime. What these cases reveal is a serious if lesser-known problem in the courts: how the rules of evidence contribute to racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Federal and state courts have rules requiring that all evidence — every crime scene photo, DNA sample, witness testimony — be deemed reliable and relevant to the crime at hand before it is shown to a jury. The strength of these rules, however, ultimately rests on the discretion of judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys. Each side makes its case as to how the rules should apply to a particular piece of evidence; the judge makes the final call. Cases like Mr. Canady’s can hinge on interpretation — whether a police officer, prosecutor, judge or jury sees the lyrics as creative expression or proof of a criminal act.

Courts typically treat music and literature as artistic works protected under the First Amendment, even when they contain profane or gruesome material. The small number of non-rap examples that I found — only four since 1950 — involved defendants whose fiction writing or lyrics were considered to be evidence of assault or violent threats. Three of those cases were thrown out; one ended in a conviction that was overturned.

Research has shown that rap is far more likely to be presented in court and interpreted literally than other genres of music. A 2016 study by criminologists at the University of California, Irvine, asked two groups of participants to read the same set of violent lyrics. One group was told the lyrics came from a country song, while the other was told they came from rap. Participants rated whether they found the lyrics offensive and whether they thought the lyrics were fictional or based on the writer’s experience. They judged the lyrics to be more offensive and true to life when told they were rap.

“The findings suggest,” the authors wrote, “that judges might underappreciate the extent to which the label of lyrics — and not the substantive lyrics themselves — impact jurors’ decisions.” Simply describing music as rap, they concluded, is enough to “induce negative evaluations.”

The Irvine findings mirrored those of a study conducted by Stuart Fischoff, a psychology professor at California State University, Los Angeles, almost 20 years earlier. Dr. Fischoff presented 134 students with one of four scenarios about a young man and asked them to rate their impressions of him across nine personality traits, including “caring-uncaring,” “gentle-rough” and “capable of murder-not capable of murder.”

The first scenario described “an 18-year-old African American male high school senior,” a track “champion” with “a good academic record” who made “extra money by singing at local parties.” The second scenario described the same person but added one detail: “He is on trial accused of murdering a former girlfriend who was still in love with him, but has repeatedly declared that he is innocent of the charges.” The third scenario did not mention the murder but instead asked the participant to read a set of rap lyrics by the young man. The fourth mentioned both the murder and the lyrics.

Dr. Fischoff found that the participants who read only about the lyrics reacted more negatively to the young man than the group who had read only about the alleged murder. “Clearly,” he wrote, “participants were more put off by the rap lyrics than by the murder charges.”

At Mr. Canady’s trial in 2016, prosecutors presented evidence that was largely circumstantial. A firearms examiner testified that one of two guns the police found in Ms. Farrington’s apartment, an unloaded .38-caliber revolver, matched the type that the police believed killed Mr. McClain, but conceded there was no way to be certain it was the same gun. Mr. McClain’s cousin testified that he had seen the victim carrying a gun he described as a “black .380,” which prosecutors proposed was similar to the other gun — a loaded pistol — found in Mr. Canady’s home. The government’s theory was that Mr. Canady had killed Mr. McClain and stolen his gun.

But no witness or physical evidence placed Mr. Canady at the crime scene. Mr. McClain’s cousin said that he saw the victim argue with a young man on the day of the murder. He noted that Mr. Canady was one of several people present but not part of the argument. (Mr. Canady told me that he knew Mr. McClain from the neighborhood and that they had friends in common.) A witness who had told the police that he heard Mr. McClain and Mr. Canady discussing guns denied it on the stand.

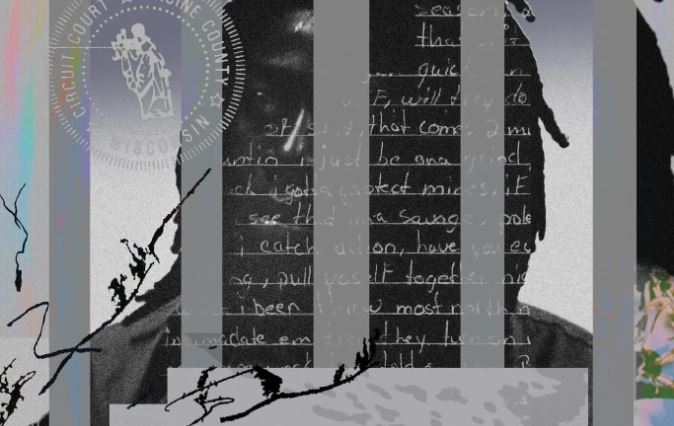

That’s where the lyrics came in. On the final day of testimony, prosecutors played “I’m Out Here” twice for the jury, first at full speed and then slowed down. A police investigator, Chad Stillman, testified that he heard Mr. Canady say “catch Semar slipping” and other lyrics that he believed alluded to the murder, including references to an alley and bullets hitting a head. Mr. Stillman also read aloud four excerpts from lyrics that Mr. Canady wrote while in jail awaiting trial — a cellmate had turned them over to officers — and interpreted their connections to the crime. “It’s consistently about shooting people,” he said. The lines “blood on my sneaks that’s from his head leaking” and “his last day i took that, im riding around with 2 straps,” Mr. Stillman asserted, referred to Mr. McClain’s head wound and the two guns found in Mr. Canady’s home

Mr. Canady tried to tell his attorney that the investigators had misheard his song, that an isolated vocal track on his computer would prove he did not name the victim. Where investigators heard “catch Semar slipping,” he said, the actual lyrics were “catch a mawg slippin’,” a slang reference to “someone on the opposite side” and a phrase that he had used in at least one other song.

During cross-examination, the defense attorney pointed out that several of the lyrics Mr. Stillman mentioned did not match the facts of the murder, including the reference to blood on sneakers, “a big Glock with 50 in it,” and an “opp car” — meaning a car belonging to a rival. (The court would later acknowledge that there were, in each of the four exhibits, “other lyrics that do not bear a resemblance to this crime.” One excerpt even ended with a critique of gun violence, in which Mr. Canady condemns all the “killing for no reason” that surrounded him.)

Asked whether he was familiar with rap composition — that boasting and violent imagery are conventions of the genre — Mr. Stillman replied, “Vaguely,” and admitted that he wasn’t sure whether rappers told the truth in their lyrics or not. “I don’t know those artists, you know, what they’ve been through,” he testified. “I know a lot of rappers come from really shady pasts where they’ve committed a large amount of crimes, and they like to brag about those crimes through their lyrics.” (Mr. Stillman, who no longer works for the department, did not reply to a request for an interview.)

Prosecutors relied heavily on the songs in their closing argument. “I think it’s best described as really a tale of two Tommy Canadys,” an assistant district attorney told the jury. “The defendant described it best in his own words,” he added, when Mr. Canady said, “‘I’m handsome and wealthy, with a monster in me.’”

During their deliberation, jurors asked to listen to “I’m Out Here” two more times. After an hour and a half, they found Mr. Canady guilty on both counts. In March 2017, just before his 18th birthday, Mr. Canady was sentenced to life in prison, with the possibility of parole after 50 years.

The rules of evidence are supposed to prohibit the presentation of “character evidence” — information that simply impugns a defendant or reveals past wrongs — to avoid biasing jurors. The use of rap lyrics in Mr. Canady’s case was an example of what legal scholars sometimes call racialized character evidence: details or personal traits prosecutors can use in an insidious way, playing up racial stereotypes to imply guilt. The resulting message, as a Boston University law professor, Jasmine Gonzales Rose, told me, is that the defendant is “that type of Black person.”

“There’s always this bias,” said Andrea Dennis, a University of Georgia law professor who has been studying the use of rap in criminal cases since the early 2000s, “that this young Black man, if they’re rapping, they must only be saying what’s autobiographical and true, because they can’t possibly be creative.” In 2016, Professor Dennis teamed up with Erik Nielson, a University of Richmond professor who studies African American literature, to compile a list of trials in which rap lyrics had been used as evidence. They found roughly 500 defendants, whose cases they discuss in their 2019 book, “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America.”

I worked with Professor Dennis to track down court documents for more than 200 of those defendants, including their race, how lyrics were used against them and the outcomes of their cases. We found more trials involving rap lyrics in the past decade than during the heyday of the war on crime in the 1990s, which suggests that the practice has become more prevalent despite a broader awareness of racial disparities in the courts and the need for reform. We identified about 50 defendants who were prosecuted using rap between 1990 and 2005, but we found more than double that number in the 15 years that followed.

It’s difficult to pinpoint a single driving force behind this trend. As some scholars have pointed out, the rise of social media, online music platforms and the popularity of rap means that the police and prosecutors have easier access to lyrics and videos. Over the years, courts that have weighed in on the matter of rap evidence have overwhelmingly ruled in favor of admitting and interpreting them literally. Of the cases where court or correctional documents specified the defendant’s race and gender, roughly three-quarters of the defendants were African American men. (Professors Dennis and Nielson note that in some states, such as California, the defendants they identified are predominantly Latino.)

While rap was rarely the only evidence presented in a case, it often played a key role in a prosecutor’s line of argument. Some used snippets of written lyrics or a recording to indicate a confession or articulate a motive. One prosecutor in California argued that lyrics from a notebook found during a search of the defendant’s home showed his intent to murder: Three round bursting real military weaponry / Leaving cold cases for eternity. Others used music videos to show that a defendant had access to a weapon similar to one found at a crime scene or that multiple defendants were in a gang. We found that courts often acknowledged that rap lyrics were prejudicial but still admitted them, concluding that their probative value was greater.

That’s what happened in Mr. Canady’s case. Before his trial, Judge Emily Mueller held a hearing to decide whether to admit several sets of lyrics Mr. Canady wrote while awaiting trial. Judge Mueller acknowledged that introducing rap lyrics to a jury unfamiliar with the genre might cause them to “think this must be some bad guy.” She considered each line in turn. Ambulance come and pick him up aint no face on em / Police come and pick me up aint got shit on me. “It does refer to the face, which I think can refer to a head shot,” she said. “The ambulance coming to pick up the person, and then police coming to pick up the writer. ‘Aint got shit on me,’ which I assume means they don’t have any evidence.” She decided to allow the lyrics because they constituted a sufficient “nexus” to the crime — an idea that’s appeared in numerous rap cases and has been criticized by some for being a meaningless standard. “While I am cognizant of the prejudice,” Judge Mueller concluded, “I don’t believe that it is undue prejudice here.” (Judge Mueller declined a request for an interview.)

Deborah Gonzalez, the district attorney who covers Athens-Clarke County in Georgia, said rap lyrics present a conundrum for prosecutors whose job is to prove guilt. She cautions those in her office against relying on rap lyrics without context or other convincing evidence, but she also sees how they could be valuable. “We’re in this Catch-22,” she said, describing trying to decide whether something was a threat or creative expression. “That’s where it sometimes gets a little iffy out there, when you can’t say that it’s 100 percent one or the other.”

Prosecutors also used rap to justify harsher sentences. In sentencing hearings, information that is off-limits during a trial, like character evidence or prior crimes, is fair game. Of the cases we reviewed, a majority of defendants went on to serve sentences of 10 years or longer; roughly a quarter received life sentences, and at least 17 people received death sentences, including Nathaniel Woods, a Black man in Alabama who was convicted of serving as an accomplice to the murder of three police officers. Mr. Woods maintained his innocence; another man, Kerry Spencer, confessed to the murder and was convicted in a separate trial. When Mr. Woods appealed his verdict, however, prosecutors countered by presenting evidence that included lyrics he was alleged to have written while in jail awaiting trial: Seven execution-style murders / I have no remorse because I’m the fucking murderer. / Haven’t you ever heard of a killa / I drop pigs like Kerry Spencer. Mr. Woods was executed in 2020. He had adapted the lyrics from a Dr. Dre song.

Evidence rules not only fail to curtail racial bias in the courts; they also enable it to thrive in plain sight. That’s why a growing number of scholars, lawyers and legislators are calling for rethinking the rules themselves. Take Federal Rule 403, which gives judges the power to exclude relevant evidence if it has a much higher risk of creating unfair prejudice or confusion, or misleading a jury. What if that rule required judges to first assess whether the burden of proof could be met without evidence like rap lyrics? Prosecutors are already asking this question in Athens-Clarke County, Ga., where Ms. Gonzalez, the district attorney, has studied Professors Dennis and Nielson’s work.

Or what if the rules simply barred rap lyrics in the first place? That’s what two New York state senators, Brad Hoylman and Jamaal Bailey, hope to achieve in a bill they introduced last fall. If passed, it would be the first to prohibit prosecutors from using rap lyrics or other creative expression as criminal evidence “without clear and convincing proof that there is a literal, factual nexus.” The bill, which has garnered support from musicians including Jay-Z, Meek Mill and Kelly Rowland, was approved in committee in January and awaits a full vote.

In 2019, two years into his sentence at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, Wis., Mr. Canady asked the court to grant him a new trial. His lawyer, Jefren Olsen, argued in a brief that Mr. Canady’s trial attorney had demonstrated ineffective counsel by failing to obtain the original recordings of “I’m Out Here” and that the judge should not have admitted the written rap lyrics in the first place.

“The parties argued a great deal” about “whether Canady’s lyrics as a whole constitute posturing and braggadocio or a representation of who he is and what he does,” Mr. Olsen wrote. The overall effect was to convince the jury of “Canady’s general bad character” without necessarily proving “his specific conduct in this case.” In July 2020, Mr. Canady finally obtained the original song mix and the isolated vocal track that he believed would give him the chance to prove his innocence.

Getting a new trial, however, requires clearing a high bar. Defendants must typically prove that the original lawyers or judge committed a serious error, and they must make a convincing case that without the error, the jury would have been likely to reach a different verdict. Arguments having to do with the interpretation of evidence do not often meet that threshold. Only Mr. Canady knows whether he is innocent. But the rest of us must ask ourselves what we’re asking jurors to judge, what we’re ultimately putting on trial, when the evidence is rap.

In May 2021, the judge who presided over Mr. Canady’s trial denied his request for a new one. (In Wisconsin, the circuit court oversees both the trial phase and the first appeal following a conviction.) Mr. Canady has since challenged the decision in the Wisconsin Court of Appeals. In a new brief, his attorney, Mr. Olsen, argues for a stricter relevance standard to be applied when the evidence in question is rap lyrics. If the appeal is successful, it could set a new precedent in the state.

Jaeah Lee is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace reporting fellow. This story was reported in partnership with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations and student researchers from the University of Georgia School of Law.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.